Please note that this summary was posted more than 5 years ago. More recent research findings may have been published.

Summary

The nature of patient needs and ward activity is changing. Inpatients tend to be more ill than they used to be, many with complex needs often arising from multiple long-term conditions. At the same time, hospitals face the challenges of a shortage and high turnover of registered nurses. This review presents recent evidence from National Institute for Health Research (NIHR)-funded research, including studies on the number of staff needed, the support workforce and the organisation of care on the wards. While few research studies have explored the similar pressures that occur in community and social care, the learning from hospitals may be useful to decision makers in these areas.

Culture or climate? ‘Climate’ describes the shared perceptions people have about their workplace while ‘culture’ refers to the beliefs, values, and assumptions that direct the behaviours of an organisation.

Shaping the team: size and mix

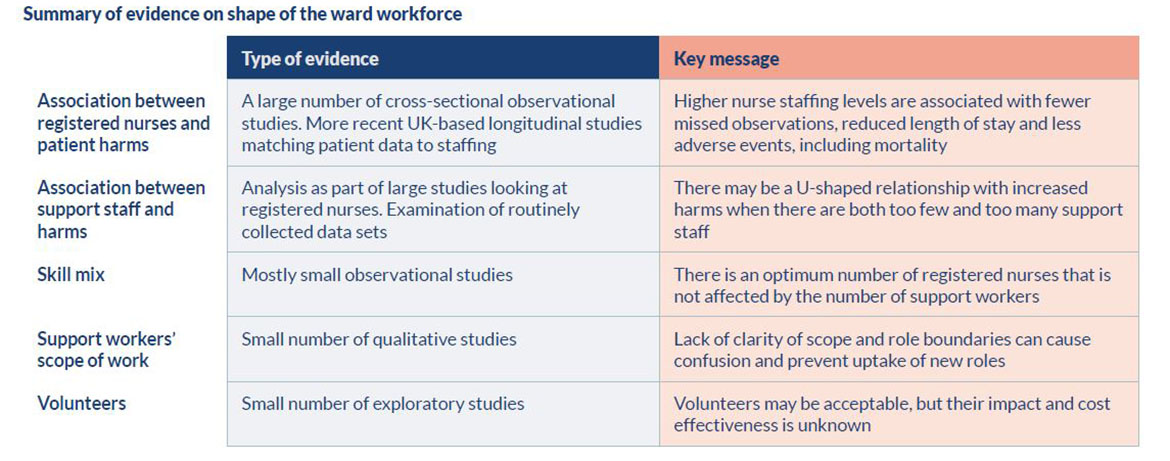

Making decisions about optimal ward staffing is complex. There is a large body of evidence, including recent UK research, demonstrating a positive relationship between the number of registered nurses in hospital wards and patient safety. The evidence suggests the relationship is not linear and we don’t yet understand enough to determine the optimum staffing levels in individual wards. NIHR studies are shedding more light on the factors that decision makers need to take into consideration.

A number of NIHR studies have looked at different support roles and identified lack of clarity around role boundaries. Research suggests that the contribution of registered nurses is distinct from that of healthcare assistants or support workers. However, the roles do overlap and the issue of how work should be distributed needs careful consideration.

Other studies have looked at the way in which nurses work with other professions to provide care on the ward and the importance of ward leadership. Research suggests emerging roles will need careful evaluation to assess their impact on care delivery and quality.

Managing the team and the ward

Planning the shape of the team is critical but managing wards well is not just a numbers game. Managers need time and training to manage staff and to use roster planning tools well. Evidence is emerging that patient experience is affected by staff wellbeing and local ward climate. Teamwork, clear role design and good local leadership all contribute to positive ward environments.

Retaining staff is as important as recruiting new people. Whilst there is a lack of evidence on interventions to do this, contributory factors tend to be multifactorial and include non-pay rewards and practice climate.

The way work is organised can have a significant impact on efficiency. There have been many interventions to improve how ward work is organised but these are often poorly evaluated and may have unintended consequences. Improvement projects are widely used in hospitals and can be effective but need careful planning and staff education to ensure sustained impact.ich nurses work with other professions to provide care on the ward and the importance of ward leadership. Research suggests emerging roles will need careful evaluation to assess their impact on care delivery and quality.

As a non-professional in the management of the NHS Healthcare sector, I found this review informative and well supported with evidential resources. As a result I now feel I have a greater understanding of the issues of ward staffing than before.

Ron Capes, Lead Governor, Basildon and Thurrock University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust

Introduction

In 2016 the NHS spent £73.8 billion on hospital services (ONS 2016), with staffing accounting for 70% of the costs (Dixon et al. 2018). Across the NHS, registered nurses and midwives make up 26.8% of all staff with healthcare support staff making up a further 15% (NHS Digital 2018a). We do not know exactly how many registered nurses and support staff work on hospital wards, but they make up a significant part of the overall hospital spend.

NHS hospitals have to balance staffing levels needed to deliver care that is safe and effective with the constraints of finite funding. New roles and changing relationships between professional groups can potentially help or hinder that balance, as can the way ward staff are managed. Research evidence can help managers to make informed and risk-based assessments about the ward workforce.

Aim and scope of the review

The aim of this review is to be informative and accessible. We provide a narrative that sets the scene through landmark studies, important new research and early work that is promising but needs further development. We hope decision makers, including senior nurses who plan and manage ward staffing on a day-to-day basis, human resource professionals, hospital managers and hospital boards and the public will find it helpful. Questions have been identified at the end of each section for organisations as a prompt to review their practice.

Our starting point for this review is research from the NIHR. This is the largest government funder of health research in the UK and includes dedicated programmes and projects on the organisation and quality of care. Working with clinicians, patients and managers, the NIHR has identified gaps in knowledge and funded new research on nurse staffing, clinical teams and improving care on hospital wards. Guided by our expert steering group, we have also included selected landmark international studies and UK-based research of interest to readers. Studies that were funded by the NIHR are identified by letters of the alphabet and a summary of each study can be found in the appendix. Other, non-NIHR, studies are cited by author name and full references given at the end of the review.

This is not a systematic review and is in part directed by the NIHR research studies available to us. We recognise the shift in policy towards healthcare provided outside of hospital and in adult social care but, at present, there is a shortage of research evidence on staffing in these areas. Hospital ward staffing remains an important issue and this review focuses on staffing within 24-hour care inpatient facilities designed to provide health rather than social care. While the available evidence is mixed in terms of research strength and generalisability, we recognise ward staffing still needs to be managed and the service cannot wait for the perfect study. Thus despite a degree of uncertainty in the evidence, we have included both large and small studies that inform decision making, including those with promising findings that need further exploration.

We describe the broad state of the evidence and highlight three NIHR-funded studies to provide more depth. We start with a background section which describes the current workforce challenges and what we know of ward staffing today.

Understanding Ward Staffing

Making decisions about ward staffing is complex. There is strong evidence linking the number of registered nurses to the rate of patient harms, including mortality. Whilst important as measures of safety, harms and mortality may not be the most sensitive indicators of adequate ward staffing. People are more than just their illnesses. The way we deliver care influences the experience of care as well as clinical outcomes. Nurse staffing has been shown to be associated with patient satisfaction as well as physical outcomes (Aiken 2018, Griffiths et al. 2018).

Ball et al. (2014) found that when staff were pressed for time, they were most likely to miss activities such as comforting, talking with and educating patients. The RN4cast study showed a link between the level of missed care and patient experience (Bruyneel et al. 2015) as well as outcomes (Ball et al. 2017). Good patient experience is positively associated with clinical effectiveness and patient safety. Doyle et al.’s (2013) review found consistent positive associations between patient experience, patient safety and clinical effectiveness across a wide range of diagnoses and care settings.

We see health systems around the world struggling with increasing demand and challenges in workforce supply. Patient safety has moved to the centre of policy and operational decision making and that means significant attention is being paid to safe nurse staffing. There are some striking core findings from across the evidence that all countries should consider, in particular the importance of nurse leadership.

Howard Catton, Chief Executive, International Council of Nurses

Providing the right number of staff is made harder when the supply of potential staff is failing to meet demand. Buchan et al. (2017) examined nurse numbers and pay policy in the UK in relation to the long term sustainability of the NHS, concluding that transformation will not be achievable without a serious examination of the way the NHS plans and uses the nursing workforce. Workforce forecasting to ensure adequate numbers of new entrants to the professions is critical, as is providing the conditions that retain experienced staff.

NHS Improvement (who license NHS providers in England) reported registered nurse vacancies as 41,772 in June 2018 out of 317,884 posts (NHS Digital 2018b). The Royal College of Nursing’s analysis show that, far from filling this gap, the supply of registered nurses will decrease over the next five years (RCN 2018). These challenges are not unique to the UK. The World Health Organisation (WHO) estimates that nurses and midwives represent more than 50% of the current shortage in health workers globally and that the world will need an additional 9 million nurses and midwives by the year 2030 (WHO 2018). This means that overseas recruitment may be increasingly difficult.

Increased access routes to becoming a registered nurse include a new type of worker, the Nursing Associate, which will be regulated by the Nursing and Midwifery Council from February 2019. The role is designed to be both a stand-alone role and to provide a progression route into graduate level nursing. It is likely that some trusts will review their skill mix to incorporate this role.

Alternative preparation for becoming a registered nurse in the UK

- Three year undergraduate nursing degree

- Two year post graduate nursing degree

- Four year nursing apprenticeship degree (since 2017)

- Two year apprenticeship Nursing Associate (a new registered role from 2019) who can then study for a further two years to gain a nursing degree

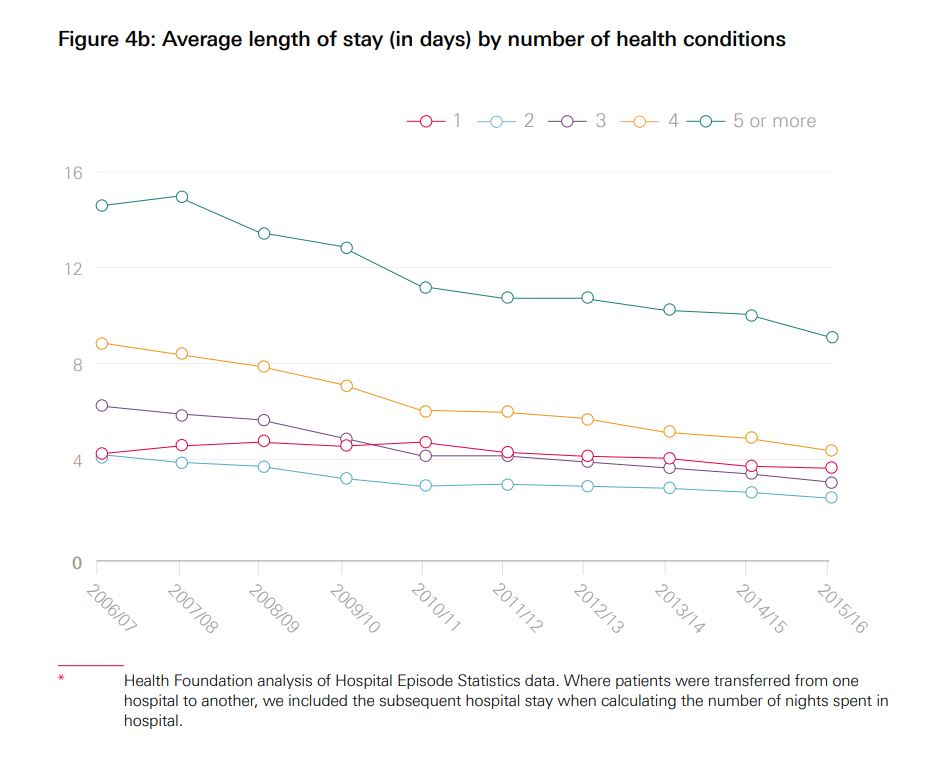

Demand for inpatient care is changing. More healthcare is delivered without an inpatient stay (e.g. day case surgery) and inpatients are having shorter lengths of stay. This means people in wards may be more acutely unwell than ever before. An increasingly ageing population, with multiple long-term comorbidities means more care is being delivered out of hospital. When people do need to be admitted to hospital, they often need more support with activities of daily living than inpatients needed in the past. On the other hand, pressures on adult social care and community services can mean some people with complex needs staying in acute hospitals longer than needed for their clinical care. Whilst they are less acutely ill, they may still need intensive help with fundamental care and ward staff may need to provide skilled rehabilitation care once their acute problems have been resolved.

Care in wards is provided by a combination of staff. A number of professions, including medical staff, physiotherapists, occupational therapists and pharmacists together with their assistant practitioners (physician associates, pharmacist technicians and therapy support workers), social workers, psychologists and specialist nurses all provide valuable input. The majority of patient contact time in wards is currently delivered by registered nurses and unregulated care assistants. The challenge of designing studies that can measure the effects of staffing in a way that takes account of the complex relationships between these diverse staff groups means that there is a gap in the evidence on professional interdependencies and the extent to which the number of staff from different professions can impact on the overall skill mix required. As a result, most of the published evidence relates to the impact of registered nurses and healthcare assistants. Each of the four countries of the UK has taken a slightly different policy approach to guidance on ward staffing (see below) and professional judgement remains important, given the differences in the many variables affecting outcomes in local contexts.

Policy guidance on determining ward staffing in the UK - brief overview

England: The National Quality Board published guidance for the NHS in England. Trust Boards are expected to agree an annual strategic staffing review, using evidencebased tools, professional judgement and comparison with peers and in line with their financial plans.

Wales: The Welsh Nurse Staffing Levels Act places a duty on Health Boards and NHS trusts to calculate and maintain nurse staffing levels in adult acute medical and surgical inpatient wards.

Scotland: A Bill for an Act of the Scottish Parliament to make provision about staffing by the National Health Service and by providers of care services is currently under consideration.

Northern Ireland: The Department of Health, Social Services and Public Services published a framework of expected ranges of nurse staffing in specific specialities. Where nurse staffing is outside the normal range, the Executive Director of Nursing must provide assurances about the quality of nursing care to these patients.

Shaping the team

The relationship between ward staffing and patient outcomes: There is strong evidence showing a relationship between ward staffing and both patient and staff outcomes. International and UK-based researchers have examined large datasets and demonstrated statistical associations between the number of patients a registered nurse cares for and a number of clinical outcomes. Limitations occur when routinely collected data are analysed alongside nurse surveys, as lags in patient data availability mean that the two data sources are not always perfectly aligned and the individual patient data is not linked to real-time staffing. However, the sample sizes in these studies and the number of studies reproducing the same findings mean the findings cannot be overlooked. A recent NIHR study published in 2018 (Study A) addresses these limitations and provides new evidence supporting a relationship between higher levels of nurse staffing and better patient outcomes.

International research has established a relationship between nursing levels and quality of care. Aiken’s seminal 2002 cross sectional study of 10,184 staff nurses and 232,342 surgical patients in the US found that for each additional surgical patient assigned to a registered nurse the odds of death increased by 7%. Similarly, Needleman et al. (2002) used data from 799 hospitals in 11 states that showed that good care is associated with both skill mix (the proportion of registered nurses) and with the total number of registered nurse hours.

The RN4Cast team (http://www.rn4cast.eu/) explored whether these findings would be replicated in Europe by testing the American findings across twelve countries and obtained remarkably similar results (see below).

Featured Study A

Higher registered nurse staffing levels were associated with fewer missed observations, reduced length of stay and adverse events, including mortality.

The authors sought to address some of the limitations in the evidence base identified by NICE by linking data at the patient level and modelling the economic impact of changes in ward staffing. This was a retrospective longitudinal observational study in one hospital in the UK. Results showed that the relative risk of death was increased by 3% for every day registered nurse staffing fell below the ward mean. Missed observations in acutely ill patients were significantly associated with lower registered nurse hours (but not support worker hours) and this was stronger on medical wards than on surgical wards. Other types of missed care were related to combined registered nurse and support worker hours but not the skill mix. This study provides high quality evidence of the relationship between staffing levels and patient outcomes. It tests a hypothesised causal mechanism and moves away from simply showing cross sectional associations.

The RN4CAST study

The European Union funded the RN4CAST team to study hospital nurse recruitment, nurse retention and patient outcomes in 12 European countries: Belgium, England, Finland, Germany, Greece, Ireland, the Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Spain, Sweden, and Switzerland. The study was conducted across 488 hospitals.

Findings from the project relating to nine of the countries (including England) include:

- An increase in a nurse’s workload by one patient increased the likelihood of an inpatient dying within 30 days of admission by 7%

- Every 10% increase in the number of degree-educated nurses was associated with a decrease in the likelihood of death of 7%

The study looked only at patients undergoing common general surgery, not all patients. The authors also acknowledged that other unmeasured factors at the individual, hospital, and community level could have affected the results (Aiken et al. 2014).

Evidence to inform guidance on ‘safe staffing’ level: Following concerns raised by the public inquiry into Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust (known as the Francis report), the Department of Health and NHS England asked the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) to develop evidence-based guidelines on safe staffing, with a particular focus on nursing staff. NICE commissioned two reviews of the evidence. The first by Griffiths et al. (2014) noted that the evidence was derived from observational studies in different countries, some of which had very different contexts and cost bases to the UK. Whilst the evidence is generally supportive of a positive relationship between staffing levels and outcomes, the fact that it is largely observational research means it is not definitive. Griffiths et al. concluded that the different contexts, outcomes, measures of staffing and methods of analysis used across the evidence made it difficult to identify safe staffing levels in the NHS with certainty.

The second review by Cookson et al. (2014) examined the cost-effectiveness of nurse staffing and skill mix on patient outcomes associated with nursing care and found only four economic studies of nurse staffing and patient outcomes, including one cost effectiveness study. None of the studies were from the UK nor did they use ward level data. The team therefore estimated effects using UK ward level data, but the poor quality of the available data limited generalisability. Neither review rejected the evidence but both found more work was needed to understand how to apply the findings in practice. Study A built on these findings and identified areas for further research, including economic analysis and the contribution of temporary staff on outcomes.

Calculating the nursing input The Carter report (Carter 2016) on productivity in English NHS acute hospitals recommended the adoption of Care Hours per Patient Day (CHPPD). This combines the total number of hours worked by both nursing support staff and registered nurses and midwives over a 24-hour period and dividing it by the number of patients in beds at 23:59. NHS Improvement requires that NHS trusts in England report registered nurse hours as a subsection of the overall score.

Other evidence on staffing and care: There is evidence that ward staffing is dynamic and that registered nurse input required varies across the patient’s stay. Study B reported statistical associations between higher numbers of registered nurses in the first week of stroke patients’ admission and increased survival, but the impact was not maintained over later stages of the patients’ inpatient stay. The short-term effect was stronger for registered nurses than support staff, suggesting there is something unique about registered nurse work at this stage of the patient journey. Twigg et al. (2016) evaluated a natural experiment in Australia which introduced an enrolled nurse (a regulated nurse role with a focus on practical nursing skills with a shorter training than registered nurses) into a system without previous experience of such a role. While the registered nurse hours stayed the same, the rate of some adverse events increased. The authors suggest this was due to lower levels of vigilance by registered nurses whose direct contact time with patients was reduced. Both Studies A and B suggest that better understanding of registered nurse work is required with careful consideration given to the relationship between registered nurses and support staff and how the work is divided. This suggests we should be cautious about combining their hours into a single measure of ward staffing provision.

Ward skill mix: Following the registration of nurses in the UK in 1919, the mix of skills in hospital wards has long been a debated area. The Lancet Commission (1932) called for more flexibility leading to the assistant nurse, later known as the state enrolled nurse, in 1943. Many countries have licensed practical nurses but the introduction in the UK of Project 2000 (UKCC 1986) saw the phasing out of the state enrolled nurse. Prior to Project 2000, hospital-employed student nurses had made up a large part of the ward workforce (supported by nursing auxiliaries) and their contribution was replaced by a new, unregulated workforce: the Healthcare Assistant. Educational preparation for unregulated staff varies from a few weeks in-house training to a foundation degree for assistant practitioners. In 2019 a new regulated role, the Nursing Associate will enter the English NHS. This raises the question of what is the most cost-effective mix of skills.

There is some evidence of the impact of support workers on patient outcomes. Jarman et al. (1999) found that higher percentages of A-grade staff (healthcare assistants) per doctor and per bed in English NHS hospitals were associated with higher mortality. However, Study A found the risk of death was higher both when there was an increase in nursing assistant hours compared to the average ward level and also when nursing assistant hours were low, suggesting a more nuanced relationship. Study C found little evidence to suggest that there was any strategic plan about how to use support workers. Senior managers largely considered the role as a substitute for registered nurses and there were multiple different titles and varying complexity and diversity of tasks performed. Whilst registered nurses valued the support roles, they had concerns around the ambiguity of role boundaries.

Our NIHR-funded study (Study C) on support workers fed into the post-Mid Staffordshire and Francis deliberations on the more efficient and effective use of healthcare assistants in acute healthcare settings. More specifically, the study provided the evidence base for the Cavendish Review, which recommended the now widely adopted Care Certificate, a more regulated and standardised approach to the induction of support workers.

Ian Kessler, Professor of Public Policy and Management at King’s College London

Northern Ireland delegation framework

The Nursing and Midwifery Council holds registered nurses accountable for decisions to delegate tasks and duties to support staff. Northern Ireland has developed a framework to help staff make a risk-based decision, taking into account the environment of practice and the professional, legislative and regulatory requirements to underpin effective decisions to delegate. The framework also helps clarify the level of supervision and support required.

http/www.nipec.hscni.net/work-andprojects/adv-guid-info-bt-pract-nurs-mid/deleg-in-nurs-mid/

Study D explored the development and impact of assistant practitioners (higher-level but unregistered support staff with foundation degree preparation) supporting the work of ward-based registered nurses in acute NHS (hospital) trusts in England. The researchers found these roles were mainly driven by external pressures rather than perceived organisational need. Individual organisations were developing roles with little national policy guidance. The consequence was diffuse and confused organisational interpretations of the role. The study found a plethora of different job titles and forms of training for assistant practitioners, which contributed to ongoing confusion about the role. The key discrepancy was the extent to which the role was envisaged as an ‘assistant’.

This need for clarity of roles is likely to extend to the use of volunteers (see below) and the communication with relatives caring for patients. Whilst there is promising evidence about the use of volunteers, some concerns have been raised about how they are used. Fitzsimons et al.’s (2014) evaluation of King’s College Hospital volunteering service found examples where boundaries between professional and volunteer roles were blurred. Ross et al. (2018) recommended hospitals adopt formal volunteering strategies that align volunteering with the organisation’s ways of working.

Evidence on the use of volunteers: The NHS is currently working to increase the scope and opportunities for volunteering in hospitals, including volunteers being directly involved with care. NIHR-funded collaborations in England have been undertaking small feasibility studies with promising findings, although large studies are needed.

Study E surveyed the views of 92 older people over a two month period about the acceptability of the use of volunteers for fundamental care of older inpatients. Most participants thought volunteers could be trained to help with meals and walking. Other tasks identified for volunteers included companionship and talking (19 responses), help tidying the bedside (16 responses), and personal care (12 responses) including washing, escorting to the toilet and cutting nails. Their main reservations were appropriate training and interaction with paid staff members.

Study F trialled the implementation of volunteer mealtime assistants in four different hospital departments (Medicine for Older People, the Acute Medical Unit, Adult Medicine and Trauma & Orthopaedics) and evaluated the practicality of recruiting, training and retaining them on such a large scale. The authors noted that including the volunteers within the ward team was crucial. Patients and ward staff valued the volunteers highly and the volunteering continued after the study finished.

Study G evaluated the feasibility and acceptability of using trained volunteers to increase physical activity of older inpatients. Volunteers encouraged patients to keep active (walk or chair-based exercises) twice a day for about 15 minutes each session. The intervention was well-received by patients and staff. Researchers noted an improvement in physical activity levels, and concluded that it was feasible and safe to train volunteers to mobilise patients. This study has since been adopted by the University Hospital Southampton NHS Foundation Trust as part of its ‘eat, drink, move’ initiative for patients.

Study H looked at the feasibility and acceptability of hospital volunteers to collect patient feedback about the safety of their care. All stakeholders were positive about the intervention and the researchers are continuing to assess the impact on patient safety improvements. A later study (Louch et al. 2018) found that although volunteer led data collection is feasible, using it to effect change was difficult and not all staff viewed it as credible safety information.

Interprofessional working: One of the criticisms of the international literature on ward staffing is the lack of reference to how registered nurses work with other professions based on the same ward. While good multidisciplinary working is widely assumed to be a positive contribution to healthcare, designing a research study to test this has proved challenging. For example, Study I synthesised nine studies that explored whether educational interventions designed to promote interprofessional collaboration improve the quality of care provided and health outcomes, but the authors decided there was insufficient evidence to draw clear conclusions on the effects. Conversely, Study J combined a review of UK and international research evidence and policy with semi-structured interviews and suggests that interprofessional collaboration and coordination of staff was associated with an increase in patient satisfaction and a reduction in length of stay.

Study K investigated the introduction of a new professional role to the UK, the physician associate, to support medical staff in secondary care. Physician associates have a first degree, are trained at postgraduate level in the medical model of care and work under the supervision of a medical practitioner. The study found they undertook much of the ward work for the medical or surgical team. Initial nurse confusion about the role dissipated relatively quickly. The continuity that physician associates provided to the medical and surgical teams as well as their presence on wards meant that nurses reported they helped early escalation of concerns about patients to senior doctors, patient management and overall patient flow.

Study L looked at stroke care pathways. It found that interprofessional teamworking was largely invisible to patients and their carers. Some of the interprofessional teams were very large and this had a number of detrimental effects, including staff feeling too intimidated to contribute; team leaders being less available; team members not knowing each other very well; and ambiguity or conflict over leadership. However, clarity of leadership was found to be highly predictive of overall team performance. The authors concluded that there is a need to consider carefully the size and structure of interprofessional teams in order to strengthen and clarify team leadership.

Are interprofessional pathways simply a series of overlapping teams? Does it matter? The authors of Study L suggest that where there was unambiguous leadership, there was better team performance. However, ambiguity in leadership was a problem identified in this study which, I believe, reflects a wider leadership crisis in healthcare delivery.

Flo Panel-Coates, Chief Nurse, University College London Hospital NHS Foundation Trust

Issues to consider when deciding the shape of the ward team: Determining the size and shape of an inpatient ward team cannot be reduced to a simple algorithm. But despite the limitations, there is a larger body of work showing a relationship between the number of registered nurse hours and safety, effectiveness and patient experience than exists for any other professional staff group. In the absence of perfect information, managers need to make decisions about the shape of the workforce, particularly in challenging economic times. The evidence presented here does not provide a definitive answer. It raises a number of critical questions for decision makers to use when making a risk-based assessment of local need:

- Do new roles change the nature of registered nurse work? Do they divert them from the direct contact and vigilance of patients that the evidence shows is critical for safety?

- Does increased input from other clinical professionals affect the amount of registered nurse hours required?

- How are unregistered workers used? Are they complementing the professions or substituting for them?

- Is there clarity within the team about the different roles, who does what and who is accountable for what? Are there clear delegation frameworks?

- Are there clear and effective systems for handing over information and following up delegated tasks?

Managing the team and the ward

Clinical productivity, or getting the best clinical outcomes for the resources provided, appears to be closely aligned with the way in which staff work together. Lalfond and Charlesworth (2017) found that hospital consultant productivity fell between 2009/10 and 2015/16 at a time of rapidly rising consultant numbers. Analysis indicated that 56% of the variation in consultant productivity at the hospital level could be explained by a number of factors, including the number of registered nurses and clinical support staff within the hospital workforce. This suggests that looking at the productivity of one professional group in isolation is unhelpful.

In addition, Dixon et al. (2018) suggest that large gains in clinical productivity can be made from good management, ensuring staff welfare and training in quality improvement methods.

Staff retention and wellbeing: Retaining staff is key, and in particular retaining experienced staff. Halter et al.’s two (2017a and 2017b) systematic reviews on the causes of nursing turnover found moderate quality evidence that nurse stress and dissatisfaction were the most significant personal issues. Managerial and supervisory behaviours were the most important organisational factors. They found the research evidence on interventions to reduce turnover was generally weak but there was some evidence that preceptorship (additional support for newly qualified staff) and good ward leadership that enhances group cohesion can decrease turnover and increase retention of nurses.

Nurses want to work in positive environments. The survey of English nurses for the RN4Cast study (Ball et al. 2012) found the strongest associations with overall satisfaction in current jobs were professional status, independence at work and opportunities for advancement.

Satisfaction and intention to stay are associated with flexible approaches to how ward staff are deployed. Study M is a systematic review of the effect of hospital nurse staffing models on patient and/or staff-related outcomes. It reported that some management systems improve staff-related outcomes, particularly primary nursing (where each patient has a named nurse to manage their care plan) and self-scheduling. However, they advise caution due to the limited evidence available. Kitson et al. (2013), in their evidence synthesis, found that a positive practice environment (based on values, professional relationships and the patient care delivery model) improved recruitment and retention. Hayward et al. (2016) reported that Canadian nurses’ decisions to leave were influenced by poor relationships with physicians and poor leadership, leaving them feeling ill-equipped to perform their job. Similar findings were observed in Italy by Galetta et al. (2013) and across 10 European countries (Heinen et al. 2013). This reflects the work of the American Nurses Credentialing Centre’s ‘Magnet’ Recognition Program. Based on work that started in 1983 identifying the 14 forces that act as a magnet to attract and retain nurses in US hospitals, this high profile accreditation system reflects the wider literature on psychology at work. However Petit and Regnaux’s (2015) systematic review of performance and quality in these hospitals found mixed results with varied research quality and could not conclude that obtaining Magnet accreditation has a causal effect on either nurse or patient outcomes.

Study N found staff morale was associated with good teamworking and amongst other findings, the researchers reported that job design factors have high influence on staff morale. While high job demands are associated with psychological strain, having a large amount of control over how the job is done can mitigate this, together with support from peers and managers. Although undertaken in mental health settings rather than acute hospitals, the findings around role definition (role clarity), fairness and communication within the team are consistent with other studies in this review.

Our research suggests that fundamental to healthcare is professionals working together to a high standard of teamwork. They must have clear, shared objectives aligned with providing high quality and compassionate care; clear roles; regular and engaging team/ward meetings; a commitment to nurture positive, supportive, compassionate relationships with each other and their patients; they must quickly work through conflict, preventing intense or chronic conflicts; value diversity; lead inter-team cooperation and, regularly take time out to review their performance and functioning and how to improve. It is not only about staffing levels but about how we work together.

Michael West, Professor of Work and Organisational Psychology, Lancaster University Management School

Good leadership and support for staff was also found to be important in Study O. This systematic review reported that staff wellbeing is linked to staff engagement and conversely a lack of engagement is associated with burnout. Job satisfaction and perceived control over own work are more likely to lead to high levels of staff engagement and there was some evidence that a highly engaged team increases the engagement of individual members. However, the authors caution that only a small proportion of studies in the review were based in healthcare settings.

The importance of local (ward) leadership and climate was also highlighted in Study P, together with the importance of education and development for staff in local leadership roles.

The importance of emotional reserves in maintaining staff wellbeing and ultimately in staff retention has led to interest in interventions to reduce emotional exhaustion. Study Q evaluated the introduction of Schwartz Rounds in the NHS. Schwartz Rounds are monthly group meetings open to all staff in healthcare organisations, where staff discuss the emotional, social and ethical challenges of care in a safe environment. Psychological health improved in staff who attended Schwartz Rounds but not in those who did not attend. Reported outcomes included reduced isolation; improved teamwork and communication; and reported changes in practice. Findings suggest Schwartz Rounds are a ‘slow intervention’ that develop their impact over time.

Featured study

Patient experience improves when staff wellbeing is high Whilst many factors influence high quality patient care, staff wellbeing was shown to be an antecedent of good patient care delivery. Patients noticed this and witnessed that staff demeanour and behaviour was linked to workplace conditions including workload, the physical environment and the way staff are managed and led. Six factors or ‘bundles’ were found to influence staff wellbeing: local (team) work climate (described by some staff participants as contributing to feelings of ‘family at work’); co-worker support, job satisfaction, perceived organisational support, low emotional exhaustion and supervisor support. Interdependencies between these different aspects of staff wellbeing meant that no single factor could be identified as the key. However, local climate was much more strongly associated with good care than organisational climate, highlighting the importance of the local work climate – peers and team and the immediate supervisor (such as ward manager) role.

Schwartz Rounds are a multidisciplinary forum designed for staff to come together once a month to discuss and reflect on the nonclinical aspects of caring for patients - that is, the emotional and social challenges associated with their jobs. Schwartz Rounds (developed by The Schwartz Center for Compassionate Care in Boston, US) are designed to foster relationships, enhance communication, provide support and improve the connections between patients and caregivers. Attending Rounds can be experienced as both supportive and transformative and staff attending Rounds report (Lown & Manning, 2010) (Goodrich, 2012):

- Decreased feelings of stress and isolation »» improved team work and interdisciplinary communication

- Increased insight into social and emotional aspects of patient care and confidence to deal with non-clinical issues relating to patients

- Changes in departmental or organisation wide practices as a result of insights that have arisen from discussions in Round

I really appreciated the language. You hear words used you don’t normally hear such as anger, guilt, shame and frustration. They are obviously there, but there is no outlet for them.

Staff participant – Schwartz Round: courtesy of the Point of Care Foundation

Case study: retaining nurses at Yeovil District Hospital

NHS Improvement in partnership with NHS Employers launched a retention programme in England in June 2017 giving trusts the tools, knowledge and expertise to develop initiatives that will encourage staff to stay working for the NHS. Yeovil District Hospital NHS Foundation Trust formed part of cohort one of the retention programme. Between June 2017 - June 2018, the trust reduced its nursing staff turnover rate by 3.3% by focussing on a number of key areas:

- Culture and leadership

- Health and wellbeing

- Personal and career development

Managing staff Decisions about the number of staff and the mix of skills use a combination of top down (e.g. benchmarking against other hospitals) and bottom up (e.g. modelling) approaches. These are often mediated by professional judgement. The demand for staff on a day-to-day basis can be highly variable. Hospitals are seeing increasing spend on unscheduled enhanced care, or ‘specialling’ (one-to-one care to ensure the safety of patients who may be suffering from cognitive impairment, exhibit challenging behaviour, or may be at risk of falls or of causing harm to themselves or others). Wood et al. (2018) reviewed the evidence and concluded there is a wide variation in what one-to-one care entails. Enhanced care is rarely mentioned when planning ward staffing requirements.

Whilst NICE endorses some resources to assist decision makers, they note that there is little evidence for the costs effectiveness of using any tool. Many of the tools are based on patient acuity rather than nursing workload (these two are not synonymous). An ongoing study (Study R) is currently evaluating one of the tools endorsed by NICE, the Safer Nursing Care Tool.

Study S explored how NHS managers use workforce management tools and technologies to determine staffing in individual hospitals. Using a variety of data sources, the researchers developed a realist program theory (a theory driven logic model with propositions that are then tested in practice). They conclude that the way tools are used is dependent on the level of commitment from leaders at all levels of the organisation. Managers need training to use these tools well and to develop their professional judgement. The researchers suggest leadership and communication skills are needed to manage the challenges resulting from the decisions they reach about staffing.

Managing the daily nurse staffing requirements within a large acute trust is incredibly challenging, with the daily reality very different to the theory used when setting establishments and skill mixes. The fast pace of an acute setting results in changing acuity over the course of the day, with the prime focus being to maintain patient safety and ensuring the right staff are available to deliver quality, therapeutic patient care. These needs have to be balanced against financial challenges and using temporary resource efficiently.

Nicky Sinden, Lead Nurse for Workforce, Portsmouth Hospitals NHS Trust

Managers also need skills to deal effectively with sickness and absences. Study T is a small study that trialled an e-learning health promotion intervention for managers to help improve employee wellbeing and reduce sickness absence. It reported managers had insufficient time to engage with the training (highlighting the need to provide ward and unit leaders with dedicated time for managing team wellbeing) and lack of senior management ‘buy-in’. In total, 21 managers used the e-learning tool, completing at least three of the six modules but wellbeing scores for staff showed little difference from the control group. The researchers concluded that the training needed to be better integrated with organisational processes and everyday practice for it to be effective.

Organising care on the wards

Staff who are engaged and enjoying their jobs also need environments where the work is effectively organised. There are many initiatives to change the way staff work. Whilst some are well evidenced, others are developed without supporting evidence and high quality evaluation. What emerges from the literature is that national initiatives are defined and implemented in highly variable ways, making evaluation of their impact challenging.

One area that has received attention is interruptions. Westbrook et al. (2017) note a steady increase in the number of studies reporting interventions designed to reduce interruptions to nurses during the preparation and administration of medications. Their study of a ‘Do not interrupt’ bundled intervention (wearing a coloured tabard when administering medications; strategies for diverting interruptions; clinician and patient education) showed the intervention was most effective at reducing interruptions from other nurses. The intervention had no substantial impact on the rate at which patients interrupted the nurse. Nurses reported a number of practical issues, including the difficulty of taking vests on and off, and concerns that medication administration took longer.

Similarly schemes to protect mealtimes (intuitively a good thing) are widely promoted. However, Porter et al.’s (2017) systematic review concluded that, given the small number of observational studies and the quality of evidence on the effect of the intervention on nutritional intake, there is insufficient evidence for widespread implementation of protected mealtimes in hospital.

The way in which the work is organised also has an impact on the efficiency of the team and staff morale.

A major initiative to improve the way in which ward care is organised (Productive Ward) was developed in 2005 by the NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement. Study U is a ten year evaluation of its impact and sustainability. The findings suggest that tools can be useful but that sustainable improvement at ward level will require additional input, including educating ward staff of all levels in the underlying principles of Lean working, and refreshing training and activities as staff and contexts change.

Featured Study U

Little quantitative evidence of sustained impact over time from Productive Ward initiative: Study U evaluated the 10-year impact of an improvement programme in English NHS trusts. Productive Ward is a quality improvement intervention developed to provide tools to engage frontline staff in the implementation of change at ward level. Based on Lean management principles, a number of modules were developed to: (1) increase time nurses spend in direct patient care, (2) improve experience for staff and patients, and (3) make structural changes on wards to improve efficiency.

A report commissioned by the NHS predicted a £270 million benefit would be yielded from implementing Productive Ward across 139 acute trusts in NHS England by March 2014. The researchers demonstrated that against this backdrop there was there was strong normative pressure on Directors of Nursing to adopt Productive Ward.

Following early adoption by a large proportion of acute hospitals in England, none did so after 2012. Adherence to the recommended approach to implementation was highly variable. The average length of use of Productive Ward was three years and a majority of Directors of Nursing surveyed said that the programme is no longer being implemented in their organisation. When the researchers conducted their fieldwork in 2017- 18, changes made to ward layouts and to specific ward processes remained evident and these were credited by study participants with improving staff and patient experience (largely through releasing time). However, there is little quantitative evidence of impact over time or whether initial improvements were sustained.

Another high profile initiative has been Intentional rounding: structured registered nurse ward rounds to address concerns about quality of care on the wards. Study V reviewed the literature, drawing on the process developed in the US whereby nurses carry out one to two hourly checks with every patient using a standardised protocol and documentation. The review highlights the ambiguity surrounding its purpose and limited evidence of how it works in practice. The researchers highlight that without good preparation and understanding of its purpose, there is potential to increase the frequency of nurse–patient communication, but not necessarily to improve its quality. Further NIHR work to evaluate practice in the UK is ongoing.

Issues to consider when managing the team on the ward: Staff morale has a direct influence over patient experience of care as well as on retention of staff. Staff morale, and staff engagement, are influenced by a range of factors including management behaviours and the ward climate. Ward climate is the shared understanding of ‘how things are done around here’ and influences the effectiveness and efficiency of specific aspects of work. There is an advantage to standardising ward processes and ensuring all ward staff have clarity of what is expected of them, but these need to be integral to the way the team work rather than bolted on. Managers and senior nurses considering how to improve the management of ward work and of the team should consider the following:

- Do we understand the ward climate and how new work processes might affect it?

- Do we link data on patient experience and outcomes to ward climate and leadership?

- What are the goals of new process and how will we know whether they have been realised?

- Do we ensure ward staff fully understand improvement techniques?

- Is the anticipated improvement worth the effort? Could the effort involved be used elsewhere with a larger gain?

Gaps in the evidence

This report is, at best, a partial review of the evidence. We know more about nurse staffing on general acute wards than we do about many other staff groups and settings, but there are still many uncertainties. Research on workforce has received relatively little funding and support in the past. This is changing and our review shows some areas where the NIHR and other research has given us good insights and understanding of the everyday challenges facing managers, staff and patients on the ward.

While we have not carried out a systematic exercise to identify gaps in evidence, there are some obvious areas where more work could be done. The research has largely focused on the link between registered nurses and a range of adverse events. Work has begun on understanding the nature of that relationship and more research is needed on the contribution of ward staff to positive outcomes and clinical effectiveness.

NICE (2014) identified the lack of economic evaluations to assess the relative value of different kinds of staff input. Whilst evidence is beginning to emerge, more studies are needed.

Most of the evidence fails to consider the contribution of other health professionals. There is a need for evidence that considers models with different levels of other healthcare professionals’ hours at ward level. The role of temporary and agency staff on the ward is also under-examined.

The role of support workers needs further exploration, including their educational preparation and supervision. Evidence is needed on where the boundaries with registered nurse work should be drawn, together with ways of supporting delegation and the flow and transfer of information relevant to patient care across the ward team.

The ward environment is changing, with the introduction of electronic records and electronic patient monitoring. A better understanding of the implications for ward staffing and workflow of new digital technology is required.

As the hospital population continues to age, with greater acuity and prevalence of other conditions such as dementia, the increasing contribution of relatives (as currently seen in paediatric wards) and the use of volunteers are both significant changes that may have material effect on the shape and work of the ward staff. Research into the risks and benefits will be needed.

Conclusion

The evidence demonstrates that making decisions about ward staffing is complex. We know that there is a relationship between the level of nurse staffing and patient outcomes, but we do not know exactly what is a safe level or the optimal skill mix of a team for individual wards. Determining the right number of staff and mix of education and skills is not a precise science and requires a risk assessment based on the best available evidence. Measuring the impact of staffing on outcomes requires robust measures that reflect the complexity. This includes further work “to develop metrics and systems that reflect wider structural factors that underpin nursing quality such as staffing, skills mix and staff experiences and link to other quality care metrics such as patient experience” (Maben et al. 2012).

There are a number of different decisions to be made about ward staffing. Firstly, the decision about the planned numbers of workers for each ward is a pragmatic decision. Decisions are based on a combination of the evidence, professional judgement and available resources (money and people). The evidence presented in this review can help to assist in the assessment of the risks associated with different staffing configurations. People making these decisions need education and training and provider organisation boards should articulate the levels of risk that they can tolerate.

Planned staffing must be matched with local decisions around fluctuating case mix and workload together with day-to-day absences in the planned staffing. The evidence shows that there are aspects of the workload which may be better undertaken by registered nurses in order to prevent avoidable patient harms, including close, direct observation of patients. Consideration of ward staffing should therefore separate registered nurse hours from assistant and support workers. The different scope of work of registered nurses, assistant practitioners and support staff together with other members of the wider team need to be clearly defined. The evidence suggests that calculations of registered nurse hours required should include sufficient time to supervise support workers. Close attention should be paid to the impact of the new nursing associate role, in particular its impact on the work of registered nurses.

Determining the makeup of the workforce is only part of the picture. Whilst there is clearly a threshold of unsafe workload, the evidence demonstrates that the way staff are managed and the work processes contribute to the staff’s capacity to provide safe and effective care. Moreover, management and ward processes have been shown to significantly influence the retention of staff. Efficient ward processes can reduce duplication and enhance staff morale, although care should be taken to avoid top down processes that conflict with local practices or increase work at ward level. The role of the ward manager has been shown to be pivotal in creating the highest levels of staff wellbeing and engagement; two factors that are key determinants of available hours on a dayto- day basis. There are a number of interventions that can help the ward manager to achieve this, from creating a positive practice environment to Schwartz Rounds as well as the management of individual staff.

It is clear that good local, real time intelligence is needed to respond to fluctuating need. The complex relationship between ward staffing and outcomes mean that there are no simple indicators that measure the impact of different staffing models. There has been research that informs decisions but its application requires managers and senior nurses with good understanding of the evidence. More work is needed to develop assurance frameworks that can encapsulate this complexity and to ensure high quality data is collected to populate them and to form the basis of future research studies.

Finally, getting the most out of staff requires good leadership to create positive ward environments and to support individual members of staff. Ward leadership shapes how staff are deployed, sets standards for staff to follow, and is key to creating a safe and healthy climate for both staff and patients. Investment in developing the skills of ward leaders to do this and ensuring they have protected time to deliver has been shown to be key in providing high quality care as well as attracting and retaining staff.

My own ward observations support the findings in the report regarding the importance of high quality leadership within wards and the value of a systematic, team environment.

Ron Capes, Lead Governor, Basildon and Thurrock University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust

Study summaries

STUDY A (HS&DR 13/114/17)PUBLISHED

Published, 2018, Principal Investigator Griffiths P

This study examined how registered nurse and healthcare assistant staffing levels relate to missed or delayed observations of vital signs (including patients’ blood pressure, pulse and breathing) and to death in hospital, adverse event (death, cardiac arrest or unplanned intensive care admission) and length of stay. It looked at data routinely collected by 32 general adult wards of an acute NHS hospital on staffing levels and electronically recorded patient observations and outcomes, involving 138,133 admissions from 2012 to 2015. Researchers found that higher registered nurse staffing levels were associated with fewer missed observations, reduced length of stay and less adverse events, including mortality. Patients who spent time on wards with fewer than the usual number of registered nurses were more likely to die, or to stay in hospital for longer. The relationship between registered nurse staffing levels and patient mortality appeared to be linear. By contrast, the effect of healthcare assistant levels was less clear, with the hazard of death increasing when patients experienced either above- or below-average healthcare assistant staffing. Although missed observations explained some of the links between nurse staffing levels and hospital death rates, there are other causal pathways so these records cannot guide staffing decisions. The authors noted that healthcare assistants are unlikely to make up for a shortfall of qualified nurses. More evidence is required to confirm approaches to setting staffing levels.

Griffiths P, Maruotti A, Recio Saucedo A, Redfern OC, Ball JE, Briggs J et al. Nurse staffing, nursing assistants and hospital mortality: retrospective longitudinal cohort study. BMJ Quality & Safety 2018. Published Online First: 04 December 2018.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs-2018-008043

Griffiths P, Ball J, Bloor K, Böhning D, Briggs J, Dall’Ora C, et al. Nurse staffing levels, missed vital signs and mortality in hospitals: retrospective longitudinal observational study. Health Serv Deliv Res 2018;6(38)

https://doi.org/10.3310/hsdr06380

STUDY B (HS&DR 12/128/48) PUBLISHED

Published, 2017, Principal Investigator Doran T

This study explored the higher risk of death of people admitted to hospital during out-of-hours periods. Researchers looked at emergency admissions data for all 140 non-specialist acute hospital trusts in England between April 2013 and February 2014 (n=over 12 million accident and emergency attendances and 4.5 million emergency admissions). They also analysed emergency admissions between April 2004 and March 2014 for one large acute NHS trust (n=240,000 admissions). They compared deaths within 30 days of attendance or admission for normal working hours and out-of-hours periods (weekends and nights). Nationally, after taking account of how sick patients were, the risk of death was no higher for patients admitted outside normal working hours, with the exception of Sunday daytimes. In one acute stroke unit, having more, and registered, nurses present during the first hours of admission was associated with increased patient survival in the first week, but not over longer periods. The researchers concluded that it is likely to be more cost-effective to extend services for key specialities over critical periods than to implement seven-day services. Future research could identify these key specialities and times.

Han L, Meacock R, Anselmi L, Kristensen SR, Sutton M, Doran T, et al. Variations in mortality across the week following emergency admission to hospital: linked retrospective observational analyses of hospital episode data in England, 2004/5 to 2013/14. Health Serv Deliv Res 2017;5(30)

https://doi.org/10.3310/hsdr05300

STUDY C (HS&DR 08/1619/155) PUBLISHED

Nature and consequences of support workers in a hospital setting

Published, 2010, Principal Investigator Kessler I

This three-year study examined the role of support workers in hospitals, particularly healthcare assistants. Senior staff were interviewed in nine NHS trusts in the south, midlands and north. Case studies of four trusts (one in each region and London) involved interviews with healthcare assistants, registered nurses and managers (n=273), observations of healthcare assistants, ward housekeepers and registered nurses (n=275 hours) and focus groups with former patients (n=94). Surveys in each trust included healthcare assistants (n=746), registered nurses (n=689) and former patients (n=1651). Findings indicated that senior managers considered healthcare assistants partly as a substitute to achieve cost efficiencies, but also as a way of relieving registered nurses of certain routine tasks. Healthcare assistants’ roles varied, with differences between trusts. Most commonly, they delivered routine technical tasks, traditionally the preserve of registered nurses. Some healthcare assistants had extended their role significantly, but were often paid at Band 2 rather than 3. Healthcare assistants were generally satisfied with their jobs. Many aspired to be nurses, but trusts did not tend to address this. Registered nurses valued healthcare assistants, although they sometimes had concerns about the delegation of tasks to them, and their accountability for them. Patients could often relate to healthcare assistants more easily than to registered nurses. Patients could not easily distinguish healthcare assistants from registered nurses but, when they could, their care experience was more likely to be positive.

Kessler I, Heron P, Dopson S, Magee H, Swain D. Nature and Consequences of Support Workers in a Hospital Setting. Final report. NIHR Service Delivery and Organisation programme; 2010.

https://www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hsdr/081619155/#/

STUDY D (HS&DR 08/1619/159) PUBLISHED

Published, 2010, Principal Investigator Spilsbury K

This mixed methods study investigated the role of assistant practitioners in acute NHS Trusts in England. Assistant practitioners are workers who have undertaken a formal qualification, for example a national vocational qualification or foundation degree. Researchers undertook case studies at three trusts, involving 13 wards. Data collection included analysis of assistant practitioner job descriptions (n=22), observations of staff activity (n=15,355) and interactions with patients (n=17,543), questionnaires (270 returned, response rate 52%), interviews (n=105) and focus groups (n=31 participants) with registered nurses, assistant practitioners and healthcare assistants. A national survey of 40 acute trusts (381 responses overall, response rate 35%), and a literature review, added context. Results indicated that organisations were developing assistant practitioner roles with little national policy guidance. Confusion about whether assistant practitioners were ‘assistants’ or ‘substitutes’ for registered nurses was compounded by inconsistency in job titles, training and pay bands. Assistant practitioners’ responsibilities fluctuated. Registered nurses were reluctant to delegate tasks due to concerns about accountability. Assistant practitioners were generally valued for contributing to patient care, providing leadership to healthcare assistants, and supporting new nurses. Opportunities for career progression seemed limited. Assistant practitioners felt that registration and regulation were important for future development of the role. Further research could evaluate the role in varying contexts, its impact on patient outcomes and its cost-effectiveness.

Spilsbury K, Adamson J, Atkin K, Bartlett C, Bloor K, Borglin G et al. Evaluation of the Development and Impact of Assistant Practitioners Supporting the Work of Ward-Based Registered Nurses in Acute NHS (Hospital) Trusts in England. Final report. NIHR Service Delivery and Organisation programme; 2010.

https://www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hsdr/081619159/#/

STUDY E (CLAHRC WESSEX) PUBLISHED

Acceptability of use of volunteers for fundamental care of older inpatients

Published, 2015, Principal Investigator Baczynska AM

This study explored the views of older people about the involvement of volunteers and family in the delivery of fundamental care in hospital. Ninety-two older people (aged 60-99 years, 74% female) were surveyed at lunch clubs (n=32 clients and 10 volunteers), a nursing home (n=11 residents) and acute medical wards in a hospital (n=38 in-patients and one relative). Forty-one respondents had experience of hospital volunteers and rated this highly. Most thought volunteers, with appropriate training, could help with meals and walking. Other tasks that some thought suitable for volunteers were: companionship and talking (n=19), tidying the bedside (n=16), and personal care (n=12) including washing, escorting to the toilet and cutting nails. Reservations included appropriate training, potential clashes with paid staff, and overcrowding on the wards. Over half of respondents would choose to regularly help paid staff in caring for a relative in hospital. Overall, the concept of volunteers and family members contributing to fundamental care in hospital was acceptable to the respondents.

Baczynska AM, Blogg H, Haskins M, Aihie Sayer A, Roberts HC. Acceptability of use of volunteers for fundamental care of older inpatients. Age and Ageing 2015 Apr; 44(suppl_1): i1.

https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afv029.01

STUDY F (CLAHRC WESSEX) PUBLISHED

Published, 2014, Principal Investigator Roberts HC

This study investigated the feasibility and acceptability of volunteers assisting older patients on an acute female medical ward with weekday lunches, over one year (February 2011 to January 2012). A volunteer training programme was developed and researchers conducted interviews and focus groups with volunteers (n=12), patients (n=9) and nursing and support staff (n=17). Of 59 potential volunteers, 38 attended a training session developed by the hospital speech and language therapist and dietitian. Volunteers were observed providing mealtime assistance, and their competency was assessed against set criteria. Twenty-nine volunteers went on to deliver mealtime assistance, including feeding, and 17 were still volunteering at the end of the year. In all, 3911 patients received assistance over the year. The authors noted that including the volunteers within the ward team was crucial. The volunteers were positive about their training and ongoing support. Patients and ward staff valued the volunteers highly. A subsequent study, from August 2014-December 2015, evaluated the wider implementation of the mealtime assistance programme in nine wards in one hospital (across Medicine for Older People, Acute Medical Unit, Trauma and Orthopaedics and Adult Medicine departments). Volunteers were trained to help patients aged 70 or over at weekday lunchtime and evening meals. Sixty-five volunteers helped at 846 meals over 15 months. A researcher interviewed patients (n=8) and staff (n=7), and conducted a focus group with volunteers (n=9). Patients and nurses universally valued the volunteers, who were skilled at encouraging reluctant eaters. Volunteers, patients and staff all saw training as essential. Cost analysis suggested that the programme released valuable clinical time. Limitations included the study being single-site.

Roberts HC, De Wet S, Porter K, Rood G, Diaper N, Robison J et al. The feasibility and acceptability of training volunteer mealtime assistants to help older acute hospital inpatients: the Southampton Mealtime Assistance Study. Journal of Clinical Nursing 2014; 23(21-22):3240-9.

https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.12573

Howson FFA, Robinson SM, Lin SX, Orlando R, Cooper C, Sayer AA, Roberts HC. Can trained volunteers improve the mealtime care of older hospital patients? An implementation study in one English hospital. BMJ Open 2018;8:e022285. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2018-022285.

https://bmjopen.bmj.com/content/8/8/e022285

STUDY G (CLAHRC WESSEX) COMPLETED, INTERIM PUBLICATIONS

Interim publications, 2018, Principal Investigator Roberts HC

This study evaluated the feasibility and acceptability of using trained volunteers to increase the physical activity of older people in hospital. Low mobility of older people in hospital is associated with poor health outcomes. Volunteers were trained to encourage older inpatients to keep active for two 15 minutes sessions per day. Activity involved walking or chair based exercises. Outcomes measured were patient activity levels, cognition, mood and quality of life. Seventeen volunteers were recruited, and 12 retained (71% retention). 310 sessions were offered, of which 230 were delivered (74% adherence). The intervention was well-received by patients and staff. Researchers noted an improvement in physical activity levels, and concluded that it was feasible and safe to train volunteers to mobilise patients. This programme, together with the mealtime assistance programme, has since been adopted by the University Hospital Southampton NHS Foundation Trust as part of its ‘eat, drink, move’ initiative for patients. From autumn 2017, volunteer mealtime and mobility assistants have been embedded in clinical services and teams, and trained and supported by University Hospital Southampton staff. Future work may include a multicentre controlled trial.

Lim SER, Dodds R, Bacon D, Sayer AA, Roberts HC. Physical activity among hospitalised older people: insights from upper and lower limb accelerometry. Aging Clin Exp Res 2018; 30(11): 1363–1369. Published online 2018 Mar 14.

https://dx.doi.org/10.1007%2Fs40520-018-0930-0

https://www.clahrc-wessex.nihr.ac.uk/theme/project/36

STUDY H (CLAHRC YORKSHIRE & HUMBER) PUBLISHED

Published, 2017, Principal Investigator O’Hara J

This study explored the feasibility and acceptability of hospital volunteers collecting patient feedback about the safety of their care, using the Patient Reporting and Action for a Safe Environment (PRASE) Intervention. The intervention involves a facilitated discussion at the patient’s bedside, and was previously explored in a randomised controlled trial. The pilot phase of the study, involving two acute NHS trusts from July 2014-November 2015, comprised five focus groups with hospital volunteers (n=15), and interviews with voluntary services and patient experience staff (n=3) and ward staff (n=4). All stakeholders were positive about the intervention, and the use of volunteers. Volunteers identified the need for appropriate training and support, while staff concentrated on the necessary infrastructure for implementation, and raised concerns about sustainability in practice. This pilot did not collect patient views. These findings informed the roll-out of the PRASE intervention to multiple wards across three NHS trusts. Researchers will evaluate this roll-out and whether the patient feedback collected by volunteers led to patient safety improvements. Louch G, O’Hara J, Mohammed MA. A qualitative formative evaluation of a patient-centred patient safety intervention delivered in collaboration with hospital volunteers. Health Expectations 2017;20(5):1143-1153.

https://doi.org/10.1111/hex.12560

STUDY I (COCHRANE EFFECTIVE PRACTICE AND ORGANISATION OF CARE GROUP) PUBLISHED

Interprofessional education: effects on professional practice and healthcare outcomes

Published, 2013, Principal Investigator Reeves S, Corresponding author Zwarenstein M

This updated systematic review added nine new studies to the six studies from a previous update in 2008. The 15 studies comprised eight randomised controlled trials, five controlled before and after studies, and two interrupted time series studies. The authors graded the quality of the evidence low to very low. All the studies measured the effectiveness of interprofessional education interventions, where members of different social and/or health care professions learn together, interactively, with the aim of improving collaboration or patient health, or both. These interventions were compared to no educational intervention. Seven studies reported positive outcomes for healthcare processes or patient outcomes, or both, four studies reported mixed outcomes (positive and neutral) and four reported no effects. The authors noted that the small number of studies, their varying design and outcome measures, and the fact that none of them compared interprofessional with profession-specific education interventions, meant that they could not draw clear conclusions about the effects of interprofessional interventions. The evidence base has grown, but further research is needed to address these gaps.

Reeves S, Perrier L, Goldman J, Freeth D, Zwarenstein M. Interprofessional education: effects on professional practice and healthcare outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013; 3:CD002213.

https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD002213.pub3

STUDY J (HS&DR - 08/1319/050) PUBLISHED

Workforce and health outcomes - scoping exercise

Published, 2004, Principal Investigator Sheldon T

This scoping study comprised a review of research evidence and policy (including from outside the UK), and 19 semistructured interviews with heads of UK health-related organisations. It assessed evidence about the impact of different mixes of medical and nursing staff on quality, clinical effectiveness, health outcomes and length of hospital stay. The policy documents and interviews suggested that the NHS, at that time, was making staffing decisions based on activity, rather than outcomes. Most of the included studies reported that better health outcomes were associated with higher doctor:patient and/or nurse:patient ratios, but the study methods had some weaknesses. Most studies suggested that patient outcomes changed little in some areas where nurses substituted for doctors, but these studies were limited in scope. Length of stay and patient satisfaction tended to improve with greater staff collaboration. Evidence on skill mix and wellbeing was limited. Overall, the variations in the methods of the studies, and poor quality evidence in some areas, made combining their results and drawing firm conclusions difficult. The authors concluded that more comprehensive research was needed to evaluate the relationship between staffing levels, skill mix and outcomes.

Hewitt C, Lankshear A, Kazanjian A, Maynard A, Sheldon T and Smith K. Health Service Workforce and Health Outcomes: A Scoping Study. Report for the National Coordinating Centre for NHS Service Delivery and Organisation.

https://www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hsdr/081319050/#/documentation

STUDY K (HS&DR 14/19/26) COMPLETED, WAITING TO PUBLISH, INTERIM PUBLICATIONS

Interim publications, 2018-2019, Principal Investigator Drennan VM This mixed methods study investigated the physician associates contribution to hospital medical teams. Physical associates are trained, following entry with a first degree (usually in biomedical science), at a post-graduate level in the medical model to undertake medical histories, physical examinations, investigations, diagnosis and treatment within their scope of practice as agreed with their supervising doctor. At the time of the study physician associates were not a regulated profession although this will change soon. This multi-phase study included: a systematic review, policy review, national surveys of medical directors and physician associates, case studies within six hospitals utilising physician associates in England and a pragmatic retrospective record review of patients in the emergency department attended by physician associates and foundation year two doctors. The surveys found a small but growing number of hospitals employed physician associates. From the case study element it was found that medical and surgical teams mainly used physician associates to provide continuity to the inpatient wards. Their continuous presence contributed to: smoothing patient flow, accessibility for patients and nurses in communicating with the doctors and releasing doctors’ (of all grades) time for more complex patients and attending patients in clinic and theatre settings and patient safety. Physician associates undertook significant amounts of ward-based clinical administration related to the patients’ care. The lack of authority to prescribe or order ionising radiation (as a non-regulated profession) restricted the extent physician associates assisted with the doctors’ workload. This study was unable to quantify the impact on service delivery or patient outcomes of one, relatively new and small, professional group within complex multi-team acute care systems and service delivery. Physician associates can provide a flexible advanced clinical practitioner addition to the secondary care without drawing from existing professions such as nurses.

Halter M, Wheeler C, Pelone F, Gage H, de Lusignan S, Parle J et al. Contribution of physician assistants/associates to secondary care: a systematic review. BMJ Open 2018;8:e019573

http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2017-019573

Drennan VM, Halter M, Wheeler C, Nice L, Brearley S, Ennis J et al. What is the contribution of physician associates in hospital care in England? A mixed methods, multiple case study. BMJ Open. 2019 Jan 30;9(1):e027012.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2018-027012